Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Fall (2006) Film Review

The Fall

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

This is a beautiful film, a visual treat from start to finish. It is allegorical, whimsical, joyous, but with an edge of sharp despair, a dark counterpoint that puts it solidly into the realm of proper fairy tales. It is a triumph.

This is only director Tarsem Singh's second film, which says nothing in and of itself, but The Fall is presented by both David Fincher and Spike Jonze. That directors of that calibre are associated with this production ought to say something, and it does: this is a film filled with staggering invention, ocular splendour. To see it on any screen other than the biggest you can is to do yourself a disservice, and to miss it is to miss a masterpiece.

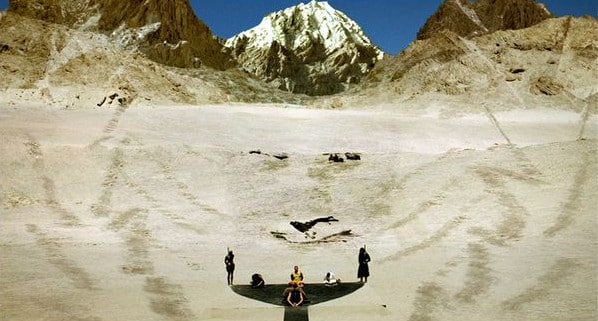

The measure of the film is its dedication to the craft of sight. There are dreams, masked bandits, pinhole cameras, silhouettes, monochrome sequences, dazzling sequences of colour and shape and movement. The only films that approach it are wuxia spectacles like Hero and fantastic confections like The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen. There are no obvious special effects: Singh has said he wanted to make a film that could have been made in 1918, and part of that is the location shots. The Fall was produced by over a dozen film units, filming in 16 countries: India, South Africa, the UK, Bali, Spain, Fiji, Prague, Italy, Romania, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, China, Turkey, Egypt, Cambodia. Each has given some aspect of itself to this tale, some abstract iconic landscape or setting, tied together in what amounts to a fable.

At the heart of this film are a young man, a child, and the story he tells to her. As with Pan's Labyrinth the gap between real and imagined is hazy, blurring from one side to another and back. He is sad, crippled, it seems, by a fall. She too is dissolute, wandering in the same Los Angeles hospital in some unknown 'once upon a time'. They meet, and he tells her a tale, of a masked bandit and his quest for revenge.

Catinca Untaru is the heart of the film as Alexandria, a girl at once precocious and beguiling, an ingenue observer. With her arm in a cast for most of the film she gives a natural performance that is utterly convincing. Her storyteller is Roy (Lee Pace), who as a suicidal young man and the brave Red Bandit wanders through her imagination and his own. The Red Bandit is accompanied by six brave companions: the freedman Otta Benga, the explosives expert Luigi, the naturalist Charles Darwin and his monkey Wallace, the Indian, and the Mystic. All have sworn vengeance on Governer Odious, and his tale is of their revenge.

Woven through the film are life in the hospital, Alexandria's adventures and misadventures within it, and Roy's attempts to come to terms with his injury and circumstances. There are falls aplenty here, from grace, from trees, from happiness. This is a film that invites reading, that is delightfully open to interpretation, without once being obscure or obfuscatory. Everything, literally it seems in terms of locations, is up there on the screen.

Tarsem's first film was 2000's The Cell, which somehow managed to convince audiences that Jennifer Lopez could travel in the unconscious of serial killer Vincent D'Onofrio in order to prevent a crime. While that film could have veered dangerously into the ground covered by Inner Space or the Saw franchise, its tone was far closer to that of Manhunter, a trip through the mind of a murderer. The Fall sets its sights even higher, examining our relation to story, to make believe, to the lies we tell ourselves and others, even to innocence.

Based (loosely) on Yo Ho Ho, a Bulgarian film from the 1980s that was itself a blending of the hospital environment and piratical action, The Fall is still full of dazzling invention. That it is a retelling simply asks further questions of the audience. The score is dominated by Beethoven's Symphony No 7, its strings recurrent and majestic, and Krishna's Levy's original contributions are tied around them.

Piled on top of all this is tremendous character design. The Bandit's band are a gleeful riot of costuming and mannerisms, all at once archaism and internal consistency, opposed by the regimented forces of Governer Odious that recall Jodorowsky's work. Slaves pull velvet carriages, gleaming red sportsters with teardrop wheel arches glisten before marble steps, even Darwin sports a coat that owes more to parakeets and A Clockwork Orange than anything else. There is no scene without something to look at and delight in, no moment that drags if the audience allows Tarsem to tell his story, and most of all: no recollection of the film is without a desire to see it again, to drink in that glorious colour and search for what may have been hidden.

Reviewed on: 25 Jun 2008